Some months ago I met a Japanese woman who, I had heard, spoke French. Being then a total beginner to Japanese, after a few sentences in Japanese I asked if we could speak in French. Her answer? 'Le francais, j'ai oublié.' It turned out that she had forgotten. The whole of French.

Three months later - this Christmas - I went to Switzerland and found myself trying to speak French.

Ordering drinks I struggled to remember basic words, even 'please' and 'excuse me', as the Japanese popped into my head more quickly. People asked me questions and I replied, unhesitatingly, with a stream of 'はい, はい, はい'. The word はい (yes) sounds the same as the English 'hi', so my stream of Japanese

perhaps made me seem like some crazy Brit with an extreme need for acknowledgement, something like

this:

French waitor: Bonjour

Me: Bonjour

FW: Would you like something to drink?

Me: はい. Coke, please.

FW: Yes, hi... Something to eat?

Me: はい, s'il vous plait.

FW: ... Is that all?

Me: はい.

FW: ...

Sentences like 'un coca, おねがいします' sometimes fell, panicked, out of my mouth.

I wasn't really speaking French or Japanese, but some conflation of what I was most used to saying in

both; basically 'Foreignese'.

It seems that there's only enough room for one studied language in my brain, and Japanese is steadily pushing

out French as sole occupant. Most likely Harry Hill has crept into my head somehow, inviting French in one

corner and Japanese in the other to: 'FIGHT!'

I don't mind. In fact I'm pretty happy at this development. In September, starting out in Japanese, to say anything

at all was a struggle. I wished I had the seven years' learning behind me that I already had in French. I've learned

two things:

(1) Immersion works. From day one, my language school spoke to me solely in Japanese. In three months

I have learned not quite, but close, to the amount I learned in seven years of French lessons.

(2) Escaping immersion pays, too. It was impossible to see that I'd progressed from within Japan, because

I was constantly using Japanese, and being made aware of how much I *didn't* know. Being in Switzerland and realising

that most of the things I could say in French I could say in Japanese, and more naturally at that, made me proud

of my Japanese.

Monday, 30 December 2013

Monday, 2 December 2013

To desu or not to desu

My mind has recently been blown (see Fig.1) by the information that です (desu), as used in sentences like:

わたし は Charlotte です

(Watashi wa Charlotte desu)

I am Charlotte

Or

そら は あおい です

(Sora wa aoi desu)

The sky is blue

Is not an equivalent of the English verb 'is', and is not actually a verb at all.

Fig.1

The 'desu' in a Japanese sentence is not a verb but, rather, just a politeness marker. In case the sentence 'the sky is blue' sounded a little rude the first time. In the sentence sora wa aoi desu (the sky is blue) the desu isn't actually needed, unless you're trying to be polite: remarking to your boss that the sky is blue, for instance (and probably receiving a withering look for wasting time..)

The は (wa) is not a verb, either. It is a particle, marking out the sentence's topic: the sky.

So the sentence translates literally as: 'as for the sky, blue'. No verb.

This leads me to my second recent realisation about the Japanese language...

Often in Japanese, words that in English we would call adjectives behave like verbs. Yes, あおい (blue) despite being called an adjective, actually acts like a verb. The result? Here in Japan, the sky blues. My bag reds. Mountains big and a mouse smalls.

This has had little impact on my actual learning of the language so far, except perhaps a slight suspicion when my teachers insist that desu must be used in every 'otherwise' verb-less sentence. I and hundreds of others are being trained to speak such polite Japanese that, apparently, we are actually identifiable on opening our mouths, by some members of the public:

'How polite, you don't happen to go to 東京日本語学校...?'

Wednesday, 27 November 2013

Man-ji

I can't help but feel that women get a raw deal, kanji-wise:

Yes, man is muscle-clad rice-provider; woman Blobbyesque Martian. Obviously.

Monday, 25 November 2013

Atatakakunakatta: or why I'm glad it's turned cold

The one consolation of the now wintery weather is that I can escape using the Japanese word for warm: あたたかい (atatakai).

Hiragana is one of three Japanese alphabets. It is used to form words which (1) have entered the language since the adoption of Chinese kanji in the 7th century, and (2) are not foreign imports (these being formed from the 3rd alphabet: katakana). Transcribed into Roman alphabet (Romaji), hiragana characters almost invariably comprise two letters, the second of which is a vowel. For instance ひ is transcribed as 'hi' (the i pronounced as in 'if'), ら pronounced 'ra', が read as 'ga', and な as 'na'. Together these create ひらがな, or hiragana.

The two-letter pairings and final vowel sound in most hiragana characters often make Japanese sound a little staccato, which brings me back to the word for warm: atatakai. Hard enough to get right in its simplest form (above), pronouncing it it the negative and past is sort of like trying to pronounce supercalifragilisticexpialidotious when you first watch Mary Poppins: the harder you try to say it the further away you get, until you give up, laughing and somehow floating near the ceiling.

My teachers ask about the weather a lot, and so I try to tell them that it is:

あたたかい - atatakai - warm

あたたかくない - atataka kunai - not warm

Or, was:

あたたかかった - atataka katta - warm

あたたかくなかった - atatakaku nakatta - not warm.

Yesterday I correctly pronounced atatakaku nakatta for the first time. I'm still quite glad that now, when the teacher asks me what the weather is like, I can say, consistently: さむいです - samui desu - it is cold.

Saturday, 16 November 2013

For Amy

I may have been slow at emails, but I have been taking some pictures to answer your question about food here! So here's a tiny snapshot...

Last week our koto (traditional Japanese harp - I'm finally learning an instrument!!) teacher gave us a bag of potatoes from Hokkaido, the northernmost island of Japan, with the instructions: たべてください - tabete kudasai, or 'please eat.' It was an unexpected but lovely present, and lacking an oven we made these:

Or, 'Hokkaido butties'. Yum.

Yesterday we visited Hakone, a mountainous region west of Tokyo where you can see monkeys (apparently) and Mt Fuji and a 'coffee and sausage restaurant.' Lunch was not coffee and sausages, but a set of vegetables, rice, pickles, and miso soup:

The little purple thing on a leaf is pudding, sweet red beans in powdered rice starch - surprisingly delicious!

Most things here that sound horrible actually aren't; for instance BBQ tea, chicken womb, this:

One thing sounds disgusting and is: natto, or sticky, slimy, fermented soy beans.

There is less sushi than I imagined, and sometimes we hunt for sushi and end up lost, confused, and eating Vietnamese food. But you can get really good sushi from the supermarket - this was 3 quid:

Properly settled in, we plan to cook more now, and today bought, amongst other things, katsuobushi (smoked dried fish shavings used to make soup etc) and Kyoto red carrots.

Here is a superhero made out of toast, to end this rambly response to your question!

Monday, 11 November 2013

Christmas is all around, Tokyo

Naively I thought that I might escape the ever elongating Christmas lead-up here in Japan. I expected that Christmas would be celebrated by a country which lays on festivities for Halloween, Valentines, St Patrick's day and everything in between, but was not prepared for the suddenness with which Christmas descended. In typical Japanese fashion the season has arrived, every bit as merry as in the UK, but far more organized.

On October 31st Shibuya was awash with orange and black; shops, restaurants and kareoke bars filled with all manner of witches, vampires, and, for some reason, pokemon characters. On November 1st the theme became decidedly more glitzy. For instance, this happened:

And (not that Starbucks is the best barometer of Japanese culture, but is ubiquitous here, and very popular among natives and gaijin alike) this:

Sitting in Starbucks - the peddler of my new addiction, Matcha Frappuccino - on November 1st, I practiced my kanji to a playlist of Jingle Bells and Wonderful Christmastime, and smiled at the sheer ridiculousness of being told to have myself a merry little Christmas on the first of November, in the still humid weather.

So Christmas fever is here in Tokyo, characteristically punctual. The actual day is quite different from Christmas in the UK, though. Friends tell me that in Japan Christmas is decidedly not a family affair. The usual thing to do on Christmas (celebrated on the 24th, and as such more in line with Scandinavia than the UK) is to go out with friends or partners to an izakaya (bar) and get wasted in a good old 'nomihodae', or all you can drink. かんぱい!

You wouldn't do this so much on New Years though - New Years here is a time to go out for a meal with your family. Oh, and hear Auld Lang Syne piped, on repeat, in department stores (though apparently that happens at other times of the year, too).

My favourite image of Christmas in Japan us one that Jim told me:

In Osaka a few years ago local authorities, decorating for Christmas, understood the festival's twin Christian (the nativity, Jesus, etc) and commercial (presents, Father Christmas) significance in the west, but not quite how these two worked together. Their municipal decoration? Father Christmas, being crucified.

Friday, 8 November 2013

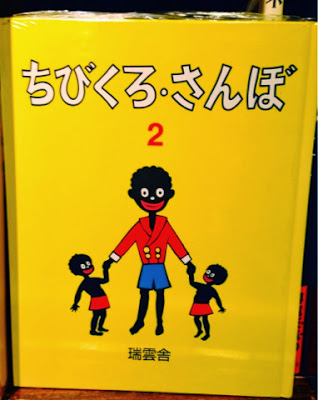

Children's literature

I found these in the children's fiction section of Tsutaya in Shibuya, shelved somewhere between Winnie the Pooh and the Moomins. It's a small section, just four or five shelves, and so each book is presumably chosen with some care. This begs the question: are these normal children's books, or am I ultra prudish?

Wednesday, 6 November 2013

The mountain who wanted to be a skyscraper

Maybe it's just me, but when I think 'mountain' I think 'rural', 'solitude', etc. Not so on Takaosan.

Men will wave sticks of soy-coated mochi at you until, will weak as tired knees on the 45 degree (paved, concrete) ascent, you finish your 'kudasai'. Agility somewhat impaired by the glutinous result of your weak will, you wonder about a break. 'Of course', Takaosan nods: 'would you prefer some shopping, a little sake, or a trip to the monkey park?' (Yes, Takaosan boasts, alongside its wild monkeys, a mini enclosure full of them. It also advertises, in capital letters, a GRASS PARK, but somehow that seemed less exciting...).

It's as if 50 years ago Takaosan grew afraid of being called old-fashioned by its new neighbour, Mr Tokyo, and decided to catch up. 'Look! I'm just like you, I have shops and restaurants and booze! I'm not like all those other mountains, those sad old things with their trees and rocks. I'm just like a street, but vertical! Sugoi desu ne?! Rooms and shops extending, scraping the sky - mark my words it'll catch on some day... '

Men will wave sticks of soy-coated mochi at you until, will weak as tired knees on the 45 degree (paved, concrete) ascent, you finish your 'kudasai'. Agility somewhat impaired by the glutinous result of your weak will, you wonder about a break. 'Of course', Takaosan nods: 'would you prefer some shopping, a little sake, or a trip to the monkey park?' (Yes, Takaosan boasts, alongside its wild monkeys, a mini enclosure full of them. It also advertises, in capital letters, a GRASS PARK, but somehow that seemed less exciting...).

It's as if 50 years ago Takaosan grew afraid of being called old-fashioned by its new neighbour, Mr Tokyo, and decided to catch up. 'Look! I'm just like you, I have shops and restaurants and booze! I'm not like all those other mountains, those sad old things with their trees and rocks. I'm just like a street, but vertical! Sugoi desu ne?! Rooms and shops extending, scraping the sky - mark my words it'll catch on some day... '

Caterium

You might assume that a cat cafe is a cafe more or less like any other, the sort of place with tables and chairs and drinks etc, just with cats dotted around. You might imagine, as I did, that a cat cafe is really a cafe for humans; a place for people who can't keep a pet to play with one for an hour or two. Really though, a cat cafe is just what it says it is: a cafe for cats. It is a place where cats eat and drink and chat and play, and humans watch them. It is a space filled with toys and scratch posts and cushioned baskets, and nothing so dull as an actual chair. People sit and lie on beanbags while cats crouch high on bookshelves, watching humans read magazines about them, and wondering whether to jump down and countenance a little affection. 'Certainly not from that man over there,' they seem to decide, 'that smiling salaryman brandishing a length of string. Too desperate. But that one over there, the one who seems actually to have forgotten about me... Has she seriously come to my cafe to talk to her boyfriend? That will not do.'

When the proprietors decide that the cats are not looking sufficiently kawaiiiiiii, it's time for the hats. The cats for their part see this as no indignity- for them it seems quite proper their nobility should be marked by these woolly crowns (which incidentally keep one's ears very toasty). They recline and watch with regal disdain the cooing humans below.

Friday, 25 October 2013

Calling all genteel gangsters

Imagine you're a Yakuza boss, and

things aren't going so well lately. Yakuza comrades (so-called kyodai

and shatei: big brothers and little brothers) are dropping out of

your family like hefty, tattoed flies. The prosthetic finger tips you

gave them haven't mollified them. Perhaps you were a little hasty to

make them say sayonara to their little finger tips, but that's the

way it's always been. 'Yubitsume', or punishment by finger-chopping,

is a centuries-old safeguard against treachery. A man grips the sword

with his thumb on one side of the hilt and fingers on the other: as

you chop off his fingertips his grip on the sword gets progressively

weaker and he becomes more dependent for his safety on his group of

allies.

But the group is declining: members

numbered around 67,000 in 2011 but dwindled to 62,000 in 2012. So

what can you do to persuade your fellow gangsters that the Yakuza is

still worth being part of; that the police crackdown on businesses

that associate with you isn't going to affect your prospects? Then it

hits you; how about a magazine written by the Yakuza, for the Yakuza?

Perfect!

Earlier this year the Yamaguchi-gumi,

one of the Yakuza's most powerful branches, published the

Yamaguchi-gumi Shinpo, an

intra-Yakuza magazine. Its pages feature interviews with Yakuza

bosses and inspirational words from Kenichi Shinoda – the head of

this Kobe-dwelling syndicate – and perhaps you'd expect these

things. More interestingly, its pages brim with fishing diaries of

senior gangsters, and haiku. I guess that sometimes when you're not

busy doing all the things that a good gangster should –

blackmailing, intimidating, hustling, gambling – you miss a good

haiku. Sometimes you wish that you had more time to pursue a pastime

as peaceful as angling, and devour descriptions of your seniors'

catches.

So,

genteel gangster, Yamaguchi-gumi Shinpo is

for you. Stick with the Yakuza: we still represent that strong,

traditional Japan that you miss. But make sure still to be on your

best behaviour; it's hard to write poetry with too many fingers

missing.

Thursday, 24 October 2013

How not to look like a cannibal in Japan

Question: Did you have a nice dinner? Seems fairly innocuous, but there are two dangerously similar answers...

Option one:

Hai, oishi katta desu

はい,おいしかったです

Yes, it was delicious

Option two:

Hai, oishii kata desu

はい,おいしいかたです

Yes, it's a delicious person.

You don't want accidentally to look like this guy:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Issei_Sagawa

Option one:

Hai, oishi katta desu

はい,おいしかったです

Yes, it was delicious

Option two:

Hai, oishii kata desu

はい,おいしいかたです

Yes, it's a delicious person.

You don't want accidentally to look like this guy:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Issei_Sagawa

Sunday, 13 October 2013

Green

Today, wandering through Higashi Matsubara, I realised that one colour can sometimes be elusive in this concrete jungle.

A word for 'green' did not originally exist in Japanese, I've been told, green being subsumed under blue for centuries with the result that apples and traffic lights are still referred to today as 'ao' - blue.

Friday, 11 October 2013

The Language Instinct Fail

Starting out as a two year old Japanese person is more difficult than I imagined, as The Very Hungry Caterpillar is proving quite heavy reading for this gaijin.

Two weeks of language school later and I can say with total confidence that:

つくえのうえにみかんがあります, phonetically 'Tsukue no ue ni mikan ga arimasu' - There is an orange on the desk.

[When I first typed this into Google translate, from Japanese to English, I typed: つくえのえうにみかんがあります - mistyping just one letter and unwittingly changing the phrase to 'Tsukue no eu ni mikan ga arimasu'. The translation read: 'There is a mandarin orange sea urchin picture desk'. Now I know two very useful phrases.]

Two weeks of language school later and I can say with total confidence that:

つくえのうえにみかんがあります, phonetically 'Tsukue no ue ni mikan ga arimasu' - There is an orange on the desk.

[When I first typed this into Google translate, from Japanese to English, I typed: つくえのえうにみかんがあります - mistyping just one letter and unwittingly changing the phrase to 'Tsukue no eu ni mikan ga arimasu'. The translation read: 'There is a mandarin orange sea urchin picture desk'. Now I know two very useful phrases.]

Saturday, 28 September 2013

The Language Instinct

Beginning to learn Japanese, recently I found myself wondering how I learned English as a child. I concluded that it was a two-stage process:

The first is immersion in the language, and by moving to Tokyo I've hopefully got that covered.

The second? はらぺこ あおむし, or:

The first is immersion in the language, and by moving to Tokyo I've hopefully got that covered.

The second? はらぺこ あおむし, or:

Saturday, 21 September 2013

Tokyo...

... Is wonderful.

and huge -

I have learned -

1. Smoking outdoors? Big no-no. Smoking indoors? Fine. Because if you choose to eat out, you choose to passive smoke, duh!

2. This - Macha Frappuccino - is delicious.

3. This is street entertainment:

3 things I learned in my first 3 days here; I can't wait to learn more.

and huge -

I have learned -

1. Smoking outdoors? Big no-no. Smoking indoors? Fine. Because if you choose to eat out, you choose to passive smoke, duh!

|

|

3. This is street entertainment:

3 things I learned in my first 3 days here; I can't wait to learn more.

Wednesday, 21 August 2013

Japan through the eyes of a six-year-old

This is not just any six-year-old, but my little (half) brother, Daniel. He often comes out with gems - some surprisingly knowledgeable and some just plain cute.

When I told Daniel that I'd be moving to Japan in September he wasn't too disheartened, figuring that since he'd be going to China anyway he could easily visit me in Japan, too. The next time he phoned he told me that he was excited to come to Japan. In a thick Barnsley accent (don't ask) he said:

'D'you know in Japan they have really, REALLY fast trains? They're so fast! They're called bullet trains. You can get one in Tokyo, where you'll be, so can we go on them when I come? I'm really excited about the trains! The trains and the kangaroos.'

So Japan according to a six-year-old? A country relatively near to China, characterised by Shinkansen and kangaroos.

|

| Daniel a couple of years ago, super happy making rice krispie cakes. |

When I told Daniel that I'd be moving to Japan in September he wasn't too disheartened, figuring that since he'd be going to China anyway he could easily visit me in Japan, too. The next time he phoned he told me that he was excited to come to Japan. In a thick Barnsley accent (don't ask) he said:

'D'you know in Japan they have really, REALLY fast trains? They're so fast! They're called bullet trains. You can get one in Tokyo, where you'll be, so can we go on them when I come? I'm really excited about the trains! The trains and the kangaroos.'

So Japan according to a six-year-old? A country relatively near to China, characterised by Shinkansen and kangaroos.

Thursday, 15 August 2013

En smak av Japan i Norge

Until I get to Japan (5 weeks and counting) I'm honing my chopstick skills whenever and wherever I can. It's sort of a race against time if I am to to eat in Tokyo.

This week I sampled sushi in Oslo, which proved both delicious and a bargain - by Norwegian standards at least. In Hasle a large box of sushi cost 109 krone; to put this in perspective half a pint of cider cost 80. Note to self: ditch the cider and spend on the sushi - good for the budget and great for chopstick hand-eye coordination.

Fersk fisk, Hvasser.

This week I sampled sushi in Oslo, which proved both delicious and a bargain - by Norwegian standards at least. In Hasle a large box of sushi cost 109 krone; to put this in perspective half a pint of cider cost 80. Note to self: ditch the cider and spend on the sushi - good for the budget and great for chopstick hand-eye coordination.

Fersk fisk, Hvasser.

Wednesday, 7 August 2013

Who's afraid of Mr Bean?

The answer? Hikari and Hiyori, a pair of identical Japanese twins.

In a lesson on British culture I asked the students which celebrities they could name, and to write which they liked and disliked. Walking around the class I saw the question 'which British celebrities do you not like, and why?' answered unanimously with 'none', or 'I like all celebrities', until I came to Hikari. Surprised, I tried not to laugh as I read her answer: 'Mr Bean, because his face is fearful'. Sitting a few seats down was Hiyori. Her answer? 'Mr Bean. His face is terrible to me'.

The idea that someone so beloved to children in Britain (and across the world) could inspire such fear in these twins (who wrote their answers independently, as far as I'm aware) at first made me giggle, and then made me think. It reminded me of an article a friend once sent me about children's stories in France:http://www.theguardian.com/books/gallery/2012/may/30/terrifying-french-childrens-books-in-pictures

Mr Bean seems so harmless next to terrifying (not to mention inappropriately sexual) titles like 'La Visite de Petite Mort'. But perhaps 'the man with the rubber face' is just as unnerving; 'l'homme au visage de caoutchouc' does have a certain ominousness to it.

In a lesson on British culture I asked the students which celebrities they could name, and to write which they liked and disliked. Walking around the class I saw the question 'which British celebrities do you not like, and why?' answered unanimously with 'none', or 'I like all celebrities', until I came to Hikari. Surprised, I tried not to laugh as I read her answer: 'Mr Bean, because his face is fearful'. Sitting a few seats down was Hiyori. Her answer? 'Mr Bean. His face is terrible to me'.

The idea that someone so beloved to children in Britain (and across the world) could inspire such fear in these twins (who wrote their answers independently, as far as I'm aware) at first made me giggle, and then made me think. It reminded me of an article a friend once sent me about children's stories in France:http://www.theguardian.com/books/gallery/2012/may/30/terrifying-french-childrens-books-in-pictures

Mr Bean seems so harmless next to terrifying (not to mention inappropriately sexual) titles like 'La Visite de Petite Mort'. But perhaps 'the man with the rubber face' is just as unnerving; 'l'homme au visage de caoutchouc' does have a certain ominousness to it.

Sunday, 28 July 2013

'Yes, yes, yes', ''Yes?" 'No', or: how I discovered aizuchi

The title of this piece is a bit misleading; really I discovered aizuchi as a child, though if someone had said the word to me I probably would have said 'Bless you'.

It sounds exotic, but 'aizuchi' is the Japanese name for something very common, namely the polite interjections in conversations which demonstrate attention and understanding: the 'yeah's and 'uh huh's that we use to show another person that we're on the same wavelength as them.

Most cultures use aizuchi to some extent and it is an important part of human relationships and conversations. The correct use of aizuchi can be pivotal in determining a conversation's 'success'. Too many interjections could be perceived as rude by some cultures, whereas too few could offend the speaker, by suggesting that the listener has switched off. However, aizuchi is a particularly important linguistic and cultural phenomenon in Japan. The word is part of a proverb 'aizuchi o utsu' (あいづちをうつ) which literally means 'striking the forge hammer'. The phrase describes the rhythmic to-and-fro of two smiths striking a hammer; as linguist Laura Miller describes it 'the alternating strikes of a mallet by a blacksmith and his apprentice'. The blacksmith makes a strike and his apprentice responds, in the same way that in a conversation one person often leads, while the other reassures the speaker that his words are understood.

Crucially in Japanese culture, aizuchi is not the same as agreement. The listener says 'yes' to indicate comprehension, not necessarily agreement. However, it is easy for non-native Japanese speakers to confuse aizuchi with agreement, as I discovered at first hand during my weeks teaching Japanese school children and collaborating with their Japanese teachers.

When not teaching, the other English teachers and I were expected to organize activities for the children, for instance sightseeing in London and Oxford. Once the students had seen Big Ben, Westminster, Buckingham Palace etc, we thought it would be nice for them to spend a day in London Zoo, to coincide with a lesson on animals. The zoo seemed to us good 'school trip' potential, and a safe place in which to let 70 Japanese children wander around and have fun. We mooted our plan to one of the Japanese teachers who spoke English, and were pleased when after every suggestion we made he said 'yes, yes, yes'. 'That's settled then', we thought, and promptly booked 70 tickets to the zoo.

Feeling happy with ourselves, we mentioned to the teacher a few days later that we were excited for the zoo, at which point he said, 'um, I've been thinking, maybe zoo, but maybe not zoo. Maybe National Portrait Gallery?' Knowing a little about Japanese culture (enough to know that the word 'no' is rarely used, but is instead implied) I quickly realised that his 'maybe not zoo' equated to a polite but resounding 'no'. The other English teachers and I could not understand his apparent volt-face, that is until I stumbled upon this article (http://www.tofugu.com/2013/06/25/aizuchi/) and reassessed our conversations mindful of aizuchi. The teacher had never wanted to go to the zoo in the first place, but from our Western perspective we assumed that his aizuchi were marks of approval, and agreement.

The situation resolved itself happily in a compromise: our zoo tickets were not wasted and we were able to see other sights on the same day, and importantly, we English teachers left with a better understanding of Japanese conversational customs.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)